Mining Money

- Aug 25, 2020

- 8 min read

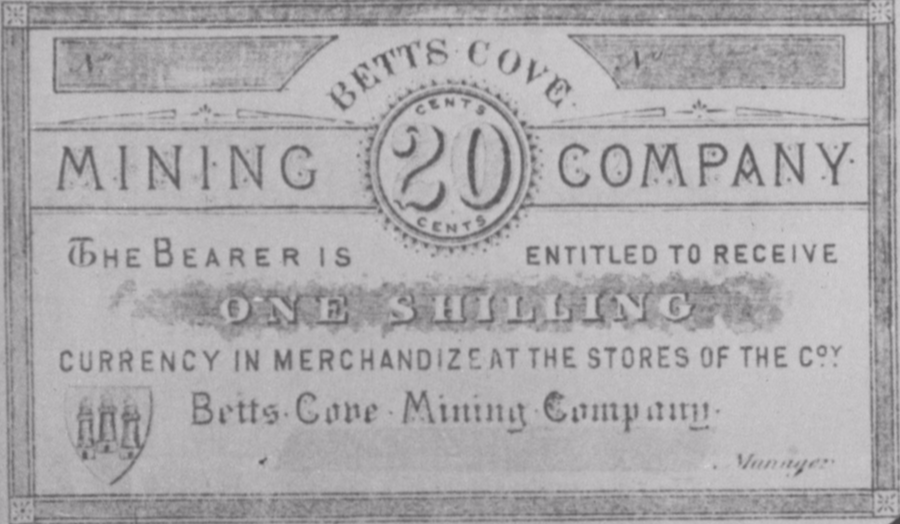

If you were a miner working in Little Bay during the late 19th century you would have had a lot of places to spend your hard earned wages. In this piece I’m going to explore the financial side of the miner’s life by considering the movement of their money. First you’ll need some context. The German Baron Franz von Ellershausen created Little Bay pretty much from scratch in 1878. He built the town; mine, mind, and man. He oversaw the layout and picked its original residents, both the high cultured leadership and the working class labourers. He paid his workers with his own script, the Little Bay script was on paper notes which likely depicted an image from the mine. Pictures of his script exist from the Bette’s Cove operation. I know of the existence of Little Bay script from a single reference in a St. John’s newspaper which listed the items lost in a missing purse. The miners were paid their script from the Company Store with the Storekeeper, Henry Lind, in charge of their income and debts as recorded in his journal. I have a photograph of a building with “Pay Office” written on it which appears to be the same building as the Lind family’s house so he may have worked from home.

The miners worked for script and the script would be used to buy goods from the Company Store. If you bought more than you could afford Mr. Lind would deduct it from future earnings. However, as Admiral Kennedy noted, during his visit in 1881, “as the men are obliged to get their provisions, clothings, &c., from the store attached to the establishment, very little cash ever reaches their pockets, I suspect” (Kennedy, P. 99). Housing was taken from wages which was also paid to the mining company. The conditions of these were poor for the first five years. It was said that “the houses in which most of the miners live at Little Bay are scarcely fit for swine to take shelter in, and the Mining Company mulet the poor fellows who live in them to the tune of four or five pounds a year as rent, and so no one can become more than a monthly tenant” (1883 Nov 30 ET). However, new housing was under construction at this time which was an expected improvement (ET Dec 1883).

Three years later, in November of 1886, a visiting journalist was “pleased to note the improved appearance which the village presented. During the past year a good many new houses have been erected” (TS Nov 1886). By this time the miners were said to have money upon money to spend and the town was described in glowing terms in various publications, for example, Little Bay was “brightened by several beautiful lakelets. Along the sea-side there are many settlers whose sandlots run back to the road, and since the latter opened many have cut roads from the cabins connecting with the main line” (DC Nov 1886). For another description of the town that year consider this passage: “Below my feet was the beautiful lake dotted with pleasure boats, just beyond — the park with its nice cottages and gardens. Seaward I beheld the harbour with Little Bay Islands in the distance [. . .] At least eighty miles of placid blue water must have been visible to me on this September day. The tints of the surrounding scenery being all enriched by the approaching autumn. It must be seen to be appreciated” (DC Sept 1886). A decade in and the town was growing steadily as people continued to arrive. The Bett’s Cove houses were “being gradually removed to Little Bay” (TS 1887 Aug).

The Baron appears to have had a rather Fordian idea of economics and for the first decade or two what benefitted the mine benefitted the men. The community flourished quickly and money started spreading around. The miners would have come to associate the Linds with getting paid. The Lind family had arrived in 1885 when Mr. Henry Lind “obtained a position as the Company Storekeeper at Little Bay mines” (Taylor, 111). His son Francis (later known by his nickname Mayo) would go on to become one of the most famous Newfoundlanders of the first World War when his letters home were published (Lind). By September 1886 Willy Lind "was working in the company store at Little Bay” with his father (Taylor, 116). The Mining Company Store was located in the Bight. Jessie Ohman described it as a good shop located on the main street. She further stated that “Little Bay is a prosperous place, the people dress fashionably, and you see no beggars, or rag-stuffed windows. About $20,000 is paid out here monthly in wages to those working at the mines. The people are independent, and have ready money” (Ohman 1892).

I am uncertain if other businesses in the community accepted the mining script but it’s a good guess that it was as good as money there. The two largest shops appear to have belonged to Johnathan Benson and the Reddin Brother’s respectfully with each employing several people. Benson’s Provisions Store was ran by Johnathan J. Benson. The Bensons lived on Otter Island but their store was located in Little Bay. It must have been on the water as it had a wharf with storage for selling salt. He was suspected of selling alcohol illegally. Hiding it in his salt stores for the McLeans. Benson had several ships built, including one by the Evans clan out of Northern Arm. His ships fished off the Labrador coast, employed people from Little Bay, and one was involved in a popular close-call. In November 1888 a silver hair fox skin was stolen from Benson’s shop by Joshua Ryan. The pelt was valued at $60.00.

Charles and William Reddin were traders and general dealers with a store situated in the Bight. They had several employees and attached to their location was McGrath’s Taylor & Outfitter shop. They employed John Martin, who in July 1886 attacked the other labourers while suffering from the delirium tremors (Wells). In October that year two seven year old boys, John Mullins and Thomas Matthews, were arrested “for having entered the shop [. . .] and stole cash valued at 10/3 (10 shillings, 3 pence) and sundry shop goods such as canned milk, canned cherries, tobacco, bottle of vinegar, cheese and biscuits” (Wells). The Reddin brothers business was expanded in June of 1888 as Charles Reddin was said to have “engaged in a new business venture, with every chance of doing well. He possesses a great advantage in starting at one of the largest cash-circulating places in the colony, and, in addition to this circumstances, he is popular with the people generally” (ET 1888 June). It was “his intention to commence a Commission and General Agency business in that community. The advantage of such an enterprise in the centre of mining operations must be obvious, and will prove of great benefit alike to consumers and those who send commodities to that market” (TS June 1888). This change was likely connected to William Reddin’s plan to retire from the business that September leaving his brother Charles solely in charge.

Benson and the Reddin brothers are well recorded but other venues are less so. One often referenced shop I know next to nothing about is the Loading Wharf Store. In fact I have next to nothing on the whole Loading Wharf area of town. I can tell you it was regarded as one of the most advanced industrial wharfage in the world, but that’s about it. There are a host of other services active in Little Bay that I’ve rarely found referenced, often only a passing line in a letter or journal. For shoes you went to the shoemaker, Allen McArthur, who could be in trouble for drinking according to the police journals. The taylor Thomas Cain found even more trouble the same way. If you wanted a new pair of boots you could go to Mr. Morris, the bootmaker. If it was a book you wanted you’d go see Mr. Brown, the bookseller. William Purchase was the watchmaker which may have been related to the jewelry shop at Lamb’s Corner. William Ross was there for your blacksmith needs while the tinsmith, Robert Malcolm, could be hungover from a night of drinking and suspected arson. He liked to burn things. Joseph Travener was a planter turned entrepreneur when he rigged up an engine to give tours around the bay, although he ran into his share of legal trouble, mostly insolvency. There is also reason to believe the Hern’s and Delany’s were in business by this time.

You could get some luxury goods imported if you had enough money. In September of 1888 while the town’s wharf was being widened to accommodate the increased harbour traffic, Mr. Burgess and Miller went into the business of meats, buying up live stock locally and importing even more. Their butcher shop was opened near The Little Bay Hotel in the Bight. There were several places to sleep and eat. The Little Bay Hotel was obviously lucrative, as was the Skittle Alley, but both ventures ended up in battle with the town’s vicious Temperance Movement. There was also something called Huxter’s Public House and Joseph Janes rented out rooms for lodgers. Several other merchants are mentioned in the Supreme Court records including; John Thorpe, John Sharp, George Stewart, William Waterman, Benjamin Boyles, William Costigan, and Thomas Stone. Thomas Boyde is listed as a dealer. Thomas Boyde is of particular note as one newspaper article about him being rescued by his daughter after falling off a wharf makes it clear that she was actively involved in the business. Thomas Boyde also went into some sort of business briefly with mine captain John Stewart and our lovelorn Dr. Joseph.

One man I’d really like to know more about was the town’s druggist, a Mr. McCarthy. I have little on him but he saved the day when the Innkeeper, Big Dan Courtney was smashed on the head and he stitched him up. I can make an educated guess that his shop supplied the town with the ointments and solutions produced by the town’s first doctor, Dr. Stafford. Stafford was gone after the first few years but created a chain of drugstores which exported various cure-alls across Newfoundland that were quite popular. I imagine his association with the early town allowed them to take some pride in his success and celebrity.

Not everyone was paid in script as not everyone worked for the mine and there were various ways to earn some extra cash. You could shoot stray dogs for example! There were many avenues for spending your extra earnings as you could book passage on a steamship, send a telegraph message to distant family, or less expensively - visit the town’s weekly Bazaar where more exotic items could be found. Those are some legal options. Illegally there was the underground gambling and booze to be found at a sheeben house, such as the operation of the infamous McLean’s.

For the first five years from 1878 to 1883 the living conditions among the working class were drawn unfavourably but by 1884 the town was regarded as fashionable and lucrative as standards rose. For the next two decades, while sometimes hindered by lulls in the mining production, it saw an overall pattern of financial improvement followed by a slow crash over the first few years of the 20th century until the fires of 1904 and 1905 just about wiped the town off the map and the history books. The once bright gem of Newfoundland faded out and was forgotten by the rest of the world. The upper class mostly saw the crash coming and got out of its way while the working class lost everything they’d gained and arrived in either St. John’s or Glace Bay to start over with nothing. The few families that remained in Little Bay to rebuild are rarely recorded but appear to have spent the next several years waiting for it all to start back up again.

I can’t help but wonder how things might have turned out if the Baron had been successful in his efforts to connect the town to St. John’s via railway and secured its survival beyond the lifetime of the mineral deposit. It’s an interesting thought and one we still wrestle with as the years from 1905 to now have seen many Newfoundland communities vanish as mining, fishing, and paper industries have failed them. Maybe someday we’ll have communities less depended on immediate financial success, or barring that, at least able to adapt to such changing conditions. Little Bay’s culture thrived not only when its industry thrived but when the leaders of its industry reinvested those profits into the town and its people. Perhaps that’s the lesson in all of this, the need for an ambitiously benevolent upper class, or perhaps we should just hold them to some responsibility. Plead or threat I guess, but either way, when we run out of food we should eat them!

Comments